ACTU Secretary Sally McManus. (AAP Image/Diego Fedele)

The trade union movement’s push to reform Australia’s enterprise bargaining system looks set to be a major issue at this week’s Jobs and Skills Summit.

The Australian Council of Trade Unions’ (ACTU) plan for sectoral or industry-level bargaining was outlined by secretary Sally McManus last week:

The way we’d see it working is that, where it makes sense to have multi-employer bargaining, both the workers’ representatives and the employers sit down and negotiate across their sector.

Innes Willox, chief executive of Australian Industry Group, labelled the proposal “seriously misguided” and a “throwback” to the 1960s. He warned it “would reduce opportunities for employers and employees to negotiate genuine improvements in productivity and work conditions that suit their workplace”.

But employer groups’ reactions have been far from unanimous.

The Council of Small Business Organisations Australia has agreed to work with the ACTU on industry bargaining reforms. The council’s chief executive, Alexi Boyd, said:

The current bargaining system was not built for us. It is not efficient and is too complicated. We welcome the opportunity to explore new flexible single- or multi-employer options that can be customised to our circumstances. The one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t work.

What is industry bargaining?

Industry bargaining is a common approach to wage negotiations in most European countries. It involves representatives of workers and employers negotiating over the pay and conditions to apply across specific sectors of the economy.

New Zealand is in the midst of introducing a form of industry bargaining through its Fair Pay Agreements Bill, currently before the NZ parliament.

An industry-level approach to award wage negotiations also operated in Australia up to the early 1990s, before the Hawke-Keating government introduced enterprise bargaining (negotiating agreements by workplace).

Enterprise bargaining is broken

Hawke and Keating saw enterprise bargaining as the way to modernise the industrial relations system in line with their mission to make Australia globally competitive.

But 30 years on, it is not delivering for employers or workers.

Unions can be involved in enterprise bargaining where they are strong enough. However, in many workplaces there is no negotiation. The employer simply puts out its proposed agreement for a vote by the employees, then submits it to the industrial relations umpire (the Fair Work Commission) for approval.

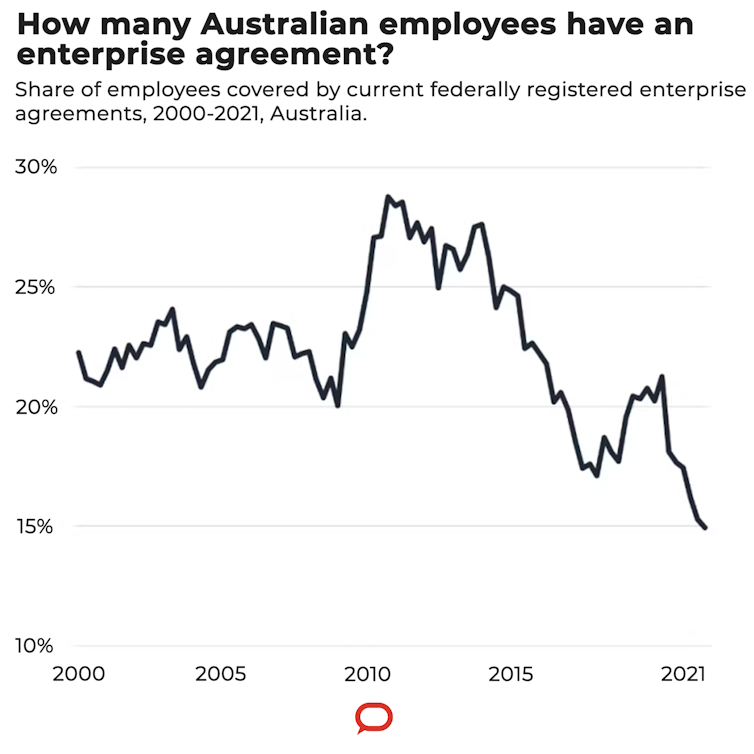

It has become increasingly apparent over the past decade that enterprise bargaining is broken. In 2012, 27% of employees were covered by an enterprise agreement. By 2021 it was just 15%.

Fears of militant unions

A major concern of business advocates such as the Australian Industry Group is that industry bargaining — backed by the right to take industrial action — will further empower unions such as the Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union to pursue “pattern bargaining” claims — by which a union secures gains from one employer and then demands the same from others.

There is indeed a risk that extending the right to bargain and strike across industries will add to the potency of some already powerful unions.

But this cannot be the perennial excuse for doing nothing to give greater leverage to hundreds of thousands of low-paid workers, doing the vital work that keeps our economy and society functioning.

The ACTU’s proposal will not be a return to the 1960s or ‘70s, when union membership was more than 50% of the workforce and there were regular strikes in support of wage demands.

In those days, unions were able to push for better pay and conditions through adjustments to awards, overseen by the industrial relations court, the Conciliation and Arbitration Commission. Awards no longer serve that purpose, now being a “safety net” for workers on minimum wages.

Why care workers would benefit

Changing the Fair Work Act to enable industry bargaining would particularly benefit workers in industries such as child care, aged care and disability support.

These are highly feminised sectors where enterprise bargaining has not delivered for a variety of reasons — including the role of government funding in setting wages, and workers’ reluctance to take industrial action that is detrimental to their clients. This has led to care workers being stuck on award-level wages.

Industry bargaining would enable funding bodies to be brought into pay negotiations in these sectors.

It would also enable workers and unions to negotiate with other business entities beside direct employers that have influence over the wages ultimately paid to employees.

This is important given the use of franchising structures, labour hire arrangements and complex supply chains to obscure the employment relationship between the worker and the business employing their labour.

To take one example, a union representing cleaners and security guards working out of the same CBD building must currently make separate agreements with the different contracting firms that employ those workers.

Industry-level collective bargaining could improve outcomes for workers in the care sector and where labour-hire and contracting practices are common. Shutterstock

In a system of multi-employer bargaining, the building owner or building services management company — which ultimately benefits from the workers’ labour and determines its price through the contracts it makes with the cleaning and security companies — would be brought into the equation.

In this way, industry or multi-employer bargaining would ensure a level playing field.

Businesses would not have to fear a competitive disadvantage from having to pay higher wages than rival businesses. Nor could they undercut each other by outsourcing to avoid higher wages and conditions in an agreement.![]()

Anthony Forsyth is a distinguished professor of Workplace Law at RMIT University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

This article is part of The Conversation’s series looking at Labor’s jobs summit. Read the other articles in the series here.

Handpicked for you

Mark McKenzie: ‘Multi-employer’ not ‘industry-wide’ bargaining needed for workplace relations reform

COMMENTS

SmartCompany is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while it is being reviewed, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.