Source: Unsplash/CHUTTERSNAP

The best word to describe the way Australia taxes alcoholic drinks is “incoherent”.

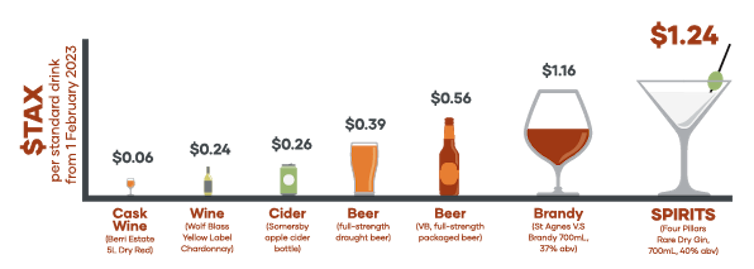

It was the word used by the 2010 Henry Tax Review to describe a system in which some wine effectively faces no alcohol tax, expensive wine is taxed heavily and cask wine lightly, beer (but not wine) is taxed by alcohol content, brandy is taxed less than other spirits, and cider is taxed differently to beer.

Industry calculations suggest cask wine is taxed at as little as six cents per standard drink, mid-price wine at 26 cents, bottled beer at 56 cents, and spirits at $1.24.

And yet it is cask wine that is often said to do the most damage.

The Henry Review recommended taxing all drinks containing more than a small amount of alcohol at the same rate per unit of alcohol, regardless of type. It was a recommendation backed by specialists in Australia’s tax system.

Implicit, and largely unexamined, in these recommendations is the assumption that alcohol does the same damage in whatever form it is taken.

Our new study, linking drinkers’ risky behaviours to the types of alcoholic beverages they mostly consume, finds this isn’t so.

Damage depends on the type of drink

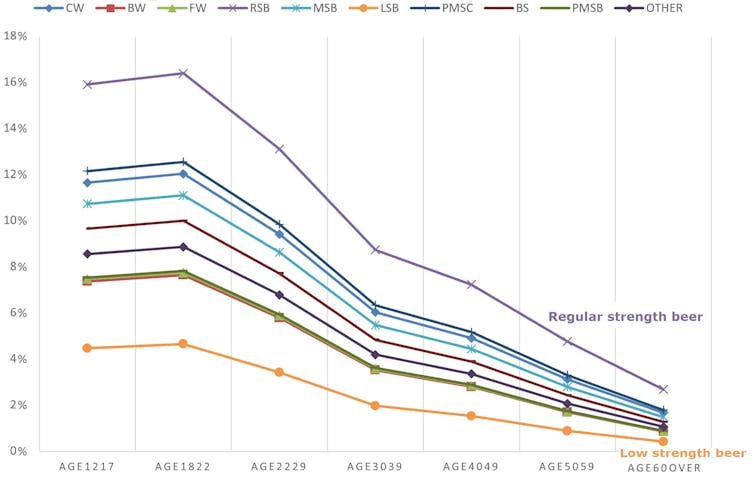

Using data from six waves of an Australian recreational drug survey, we find that regular-strength beer and pre-mixed spirits in a can rank among the highest in their links to both drink-driving and hazardous, disturbing or abusive behaviours.

Mid-range are mid-strength beer, cask wine, and bottled spirits and liqueurs.

At the bottom are low-strength beer and pre-mixed spirits in a bottle, which have the weakest links to risky and abusive behaviours when intoxicated.

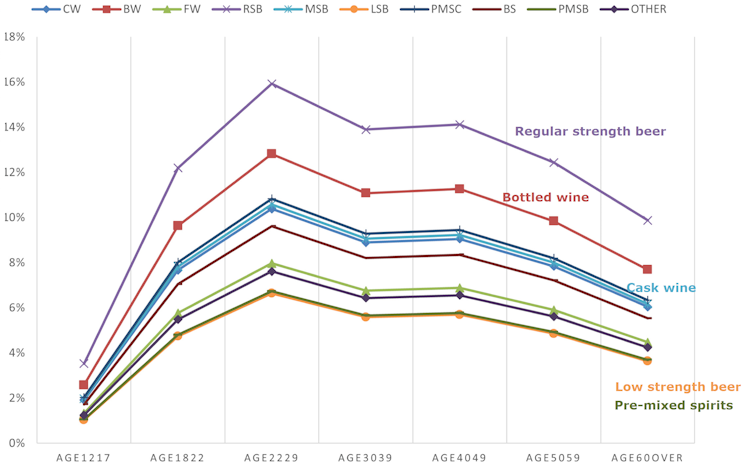

Probability of drink driving, by age and beverage type

Some of the relationships vary with the type of damage. While bottled wine is linked to a moderate to high probability of drink-driving, it is also linked to a low probability of hazardous, disturbing or abusive behaviours.

Pre-mixed spirits in a bottle are related to a low probability of both drunk driving and hazardous, disturbing and abusive behaviours. But when account is taken of the gender of the drinkers (so-called alcopops are typically drunk by females), we find them no longer as safe.

Probability of hazardous, disturbing or abusive behaviour

Our study suggests that Australia’s haphazard system of taxing alcohol might have got some things right. Beer, which is typically taxed more highly than wine, seems to do more damage.

But it has got some things wrong. Cask wine appears to be significantly undertaxed relative to the damage it does.

More broadly, our findings suggest that if alcohol is to be taxed according to the damage it does, the tax system we adopt will need to be more complicated than a single rate for every unit of alcohol regardless of the form in which it comes.![]()

Ou Yang is a research fellow at the University of Melbourne and Preety Pratima Srivastava is a senior lecturer at RMIT University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Handpicked for you

“Tread carefully”: ATO warns taxpayers relying on AI-generated information

COMMENTS

SmartCompany is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while it is being reviewed, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.