Melbourne's Queen Victoria Market. Source: Unsplash/Linda Xu

Australia’s economy will limp along after recovering from the pandemic, failing to regain the growth it had either in the years leading up to the crisis or the much higher growth in the decades before.

That’s the consensus of the 23 leading Australian economists assembled to take part in The Conversation’s July 1 forecasting survey — a panel that includes former Treasury, Reserve Bank and International Monetary Fund officials and modellers, as well as policy specialists from 13 Australian universities.

On balance, the panel expects year-average economic growth (the measure reported in the budget) to slide from 4% this financial year to just 2.2% by 2024-25, well below the average of 2.6% assumed in this week’s intergenerational report.

The panel forecasts much weaker business investment than does the budget and lower household spending, but higher wage growth and lower unemployment. It expects a flat share market, and slower growth in house prices.

Weaker economic growth

During the decade leading up to the COVID-19 crisis, economic growth averaged 2.6% per year. During the 27 years between the early 1990s recession and the crisis, it averaged 3.2%.

The panel’s average forecast of 2.2% by the end of the four-year budget forecasting horizon is lower than both the budget forecast of 2.5% and the 2.6% in the intergenerational report.

Economic modeller Janine Dixon expects growth of just 1.7%. She says after Australia has soaked up unemployment, its future economic growth can only be driven by population growth or improved productivity.

With population growth expected to be weak for several years, GDP growth will be weak unless dwindling productivity growth rebounds.

Forecasting veteran Saul Eslake says, on the other hand, for as long as borders remain closed Australia should enjoy an “artificial boost” to domestic spending of more than $50 billion per year from Australians who can’t spend abroad.

The two most optimistic forecasts of 3% growth, from Angela Jackson and Sarah Hunter, are contingent on borders reopening and tourism and immigration restarting.

The panel expect extraordinarily strong growth in the United States of 5.2% throughout 2021 on the back of what panelist Warren Hogan calls massive government stimulus and a full-vaccination rate approaching 50%.

China’s growth is forecast to rebound to 7.9%, but will come under pressure from what panelist Mark Crosby describes as an attempt by some of China’s customers to diversify the sources of supply away from China.

Support from iron ore

The panel expects actual living standards to be higher than the bald economic growth figures suggest.

This is because high iron ore prices boost Australians’ buying power (by boosting the Australian dollar) and boost company profits in a way that isn’t fully reflected in gross domestic product.

In recent months, the spot iron ore price has been at a record US$200 ($266) a tonne, a high the budget assumes will collapse to near US$63 by April next year as supply held up in Brazil comes back online.

The panel is expecting the iron ore price to stay high for longer than the Treasury — for at least 18 months, ending this year near a still-high US$158 a tonne.

There’s agreement that at some point the unusually high price will fall, with one panelist saying there might be “one more year to ride this wave, then who knows”.

Because the panel expects a higher iron ore price than the government in the year ahead, it expects a greater rise in nominal gross domestic product — the measure of cash pouring into wallets. The panel forecasts an increase of 5% this financial year compared to the budget forecast of 3.5%.

But it expects consumer caution to limit growth in household spending to 4.2%, much less than the budget forecast of 5.5%.

Unemployment to fall quickly

The panel expects unemployment to fall more quickly than the government does, to 4.7% by mid-2022 — a low the budget didn’t foresee until mid-2023.

The unemployment rate is already 5.1%, something the May budget didn’t expect for a year. However, it is to some extent artificially assisted because jobs that used to go to temporary foreign workers and were not counted in the employment statistics are now being taken by domestic workers who are counted.

As foreign workers return to Australia, the process will unwind, putting upward pressure on the recorded unemployment rate.

Wage growth better than budget

The May budget forecast wage growth of just 1.5% in 2021-22 (less than forecast price growth), followed by only 2.25% in 2022-23 (merely matching price growth), in part because of legislated increases in employers’ super contributions.

The forecasting panel is more optimistic for the year ahead, being able to take account of the Fair Work Commission’s 2.5% increase in award wages announced in June.

Warren Hogan calls 2.5% the new “baseline”, with some labour shortages forcing some employers to offer more.

Even so, the panel’s average wage growth forecast for 2021-22 is 2.2%, only marginally above expected price inflation of 2.1%.

Slower home price growth

The panel expects weaker home price growth in the year ahead, with the CoreLogic Sydney price index climbing 6.4% after a year in which it soared 11.2%.

Melbourne prices should climb a further 5.2% after a year in which they gained 5%.

The panelists say much will depend on how long mortgage rates remain at their record lows, what action authorities take to restrain lending and when immigration restarts.

Low rates for some time

Over the past year, the bond rate at which the Commonwealth government can borrow for ten years has jumped from 0.9% to 1.5% in accordance with moves overseas.

The panel expects further increases to a still-low 1.8% by the end of this year and to 2.2% by the end of next year.

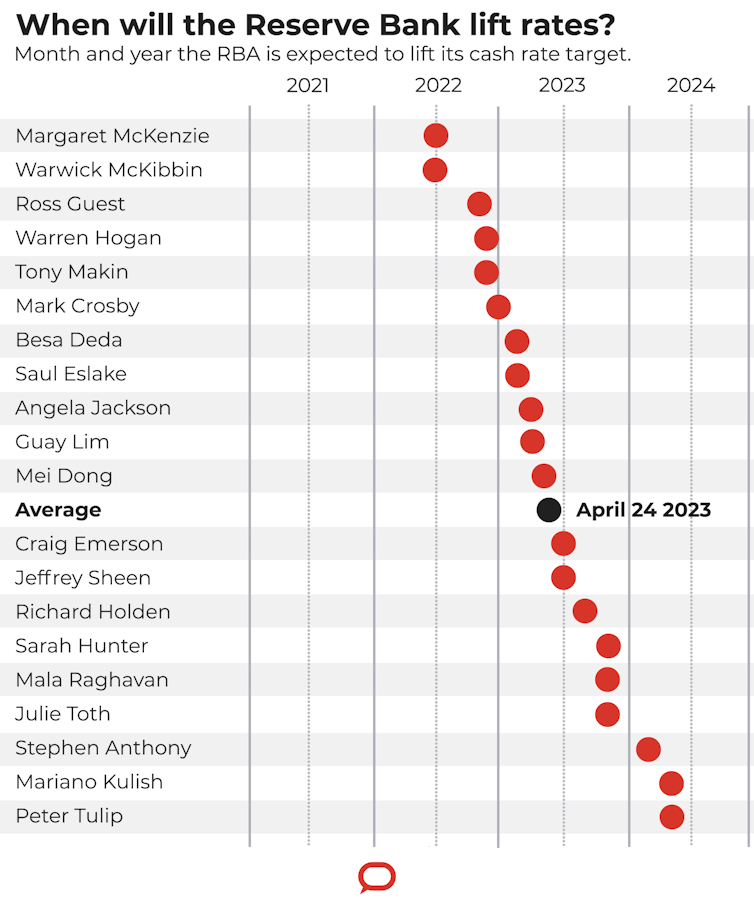

Even so, the panel expects no increase in the Reserve Bank’s cash rate — the one that drives variable mortgage rates — for almost two years, until April 2023.

Former Reserve Bank head of research Peter Tulip, now with the Centre of Independent Studies, says the bank meant it when it said it said it wouldn’t lift the record-low cash rate of 0.1% until actual inflation was “sustainably within” its 2-3% target range, something that wasn’t likely until 2024.

Other panelists, including economic modeller Warwick McKibbin, believe those criteria might be met sooner, some as soon as mid-2022.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

No take-off in investment

The panel doesn’t buy the government’s bold prediction of a jump in non-mining business investment in response to budget tax measures.

The budget predicts year-on-year growth of 12.5% in 2022-23 after 1.5% in 2021-22.

Instead, the panel predicts 3.7% in 2021-22 and 5.8% in 2022-23, citing low population growth and the likelihood that most investment that could have been brought forward by tax measures has already been brought forward.

Former IMF official Tony Makin also points to the relatively high tax rates facing foreign investors and the increasingly restrictive approach of the Foreign Investment Review Board.

Other panelists cite lack of clarity about the rules governing investment in renewable energy and growing shortages of labour and materials as reasons to expect only restrained growth in business investment.

Markets steady

On balance, the panel expects the US-Australia exchange rate to stay where it is at around 76 US cents as it has for years, noting that much will depend on the iron ore price and the strength of the US economy.

On average, it expects no change in the Australian share market after 12 months in which the ASX200 has soared 24%.

The average hides sharp differences. Some panelists expect the ASX200 to climb a further 10%, while others expect it to fall 10%. One panelist, economic modeller Stephen Anthony, expects a collapse of 55%, saying it “smells like a blood bath is coming”.

Deficits forevermore

This year’s budget forecast is for a deficit of 5% of GDP after last year’s near-record 7.8% of GDP.

Asked at what point over the next four decades the budget deficit would shrink to 1% of GDP, three panelists replied “never”.

Six others said not before 2030. Only four nominated the decade ahead.

Angela Jackson said any improvements in the budget position delivered by a better-than-expected iron ore price would be spent.

Saul Eslake saw no appetite for either the tax increases or spending cuts that would be needed to eliminate the deficit, adding that, fortunately, there was no “urgent requirement to do so”.

Unexpected times

Forecasts often don’t come to pass. This time last year, mid-pandemic in a rapidly evolving situation, the panel forecast unemployment of 8.8%, no share market growth and ultra-low wage growth of just 0.9%.

That these things didn’t happen was in part due to the role of such forecasts in persuading the government to respond in an unprecedented fashion, a point made by Treasurer Josh Frydenberg launching the intergenerational report on Monday.

This year’s forecasts, prepared in a less-hectic environment, might have more staying power. They point to a weak recovery and an economy reliant on government support for some time to come.

Participants

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Handpicked for you

Kathmandu’s $13 million lockdown hit shows how the Australian economy is falling behind

COMMENTS

SmartCompany is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while it is being reviewed, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.