Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe delivers an address to the National Press Club in Sydney on Wednesday, February 6, 2019. Source: AAP Image/Dan Himbrechts.

Never has a virus featured so prominently in a Reserve Bank statement.

The word “coronavirus” is mentioned nine times in the governor’s seven-paragraph statement.

His board cut the cash rate from an all-time low of 0.75% to a new all-time low of 0.50% “to support the economy as it responds to the global coronavirus outbreak”.

Up until the coronavirus, it had looked as if “the slowdown in the global economy that started in 2018 was coming to an end”.

The coronavirus has “clouded” that outlook.

It is “too early to tell how persistent the effects of the coronavirus will be and at what point the global economy will return to an improving path”.

Financial markets have been volatile “as market participants assess the risks associated with the coronavirus”.

In most economies, including the United States, there is an expectation of further rate cuts.

The coronavirus is having a “significant effect” on Australia’s real economy, particularly in the education and travel industries.

The uncertainty is “also likely to affect domestic spending”.

GDP growth in the March quarter (but not the December quarter whose figures will be released on Wednesday) is likely to be “noticeably weaker than earlier expected”.

Once the coronavirus is contained, the Australian economy is expected to return to an improving trend.

But given the evolving situation, it is difficult to predict how large and long-lasting the effect will be.

Summing up, the bank says the global outbreak is “expected to delay progress in Australia towards full employment and the inflation target”.

It decided to cut rates to provide “additional support to employment and economic activity”. Importantly, it will continue to monitor developments closely with a view to doing more.

The final sentence, the one which usually carries the key message, says: “the board is prepared to ease monetary policy further to support the Australian economy”.

Would it have cut without the coronavirus?

It probably wouldn’t have cut without the coronavirus. It most likely would have had to cut at some point because the economy is weak. We will get an update about how things were in the three months to December on Wednesday, but the news up to the end of September was awful.

Household spending, which accounts for more than half of gross domestic product, barely budged. Over the year to September it grew just 1.2% in real terms, the least since the global financial crisis. Australia’s population grew 1.6% in that time, meaning the volume of goods and services bought per person went backwards.

Early figures on private new capital expenditure which will be incorporated into the national accounts released on Wednesday show business investment went backwards over the December quarter (down 2.8%) and over the entire year (down

5.8%).

The May budget and the December budget update forecast a jump in business investment, which it is hard to see happening.

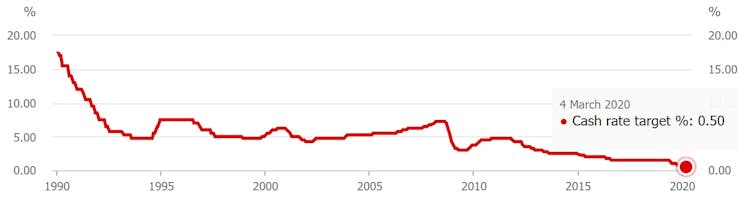

Governor Philip Lowe has been reluctant to cut in part because he is running out of traditional ammunition.

He has said that for practical purposes the next step — 0.25% — is zero, a point beyond which he would need to use unconventional measures (which have been used so much overseas they are no longer that unconventional) to stimulate the economy further.

The most likely one is buying government and mortgage bonds from investors in order to force money into their hands, making the cash rate graph the bank has been updating for 30 years now no longer relevant as an indicator of what it is doing to stimulate the economy.

Reserve Bank cash rate

He has decided to cut because he is contractually obligated to do what he can to contribute to “the economic prosperity and welfare of the people of Australia”, which is at risk.

What good will the cut do?

Westpac and the Commonwealth Bank announced they were passing the cut on to borrowers straight away after an appeal by Prime Minister Scott Morrison to their better natures.

“The government would absolutely expect the four big banks to come to the table and to do their bit in supporting Australians as we go through the impact of the coronavirus. I don’t see it any different to what Qantas did when we called out to Qantas and we said, we need your help, we need to get some people out of China.”

Before today’s decisions, the average standard variable mortgage rate was 4.7% The average basic variable mortgage rate was 3.05%. Today’s cuts will take it to 2.8%.

They will save many mortgage holders an extra $30 per month on repayments on top of the $150 saved since June. That will allow them to spend more or to borrow more by extending their mortgages, further increasing the financial attractiveness of investments such as solar panels or home insulation, and perhaps further supporting home prices which have turned up since the bank began cutting.

Where mortgage holders direct the proceeds of the cuts to Australian businesses, it’ll help keep them afloat or give them the confidence to borrow for expansion at record-low interest rates.

Although it is often said that interest rate cuts have less effect when interest rates get low, there is no particular reason to believe this is the case. There is reason to believe interest rate cuts have little effect when consumers and businesses have other reasons for not borrowing or spending much, which might well be the case at the moment.

What will the government do?

The government is drawing up a stimulus plan. Just don’t call it that.

Morrison says it will “be a targeted plan, it will be a measured plan, it will be a scalable plan, we will ensure that we do not make the same mistakes of previous stimulus measures that have been put in place”.

That probably means he won’t be delivering cheques to households as Labor did during the global financial crisis. The Coalition tried something similar, delivering out-sized tax refund cheques after the May budget, and it didn’t work that well.

He’ll almost certainly announce new investment allowances for businesses; if necessary, ones that effectively pay them to borrow.

And he and his ministers will be surveying the economy sector by sector.

He has spoken personally with the bosses of Coles and Woolworths seeking assurances they won’t run low on supplies. He says if necessary they can talk to each other, something normally not allowed by competition rules.

They have already talked to Kimberly Clark, which manufactures toilet paper. It has set up a line of production in South Australia to ensure shops don’t run out.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

NOW READ: From the lobster industry, to novelty shirt stores, who is profiting from the coronavirus?

COMMENTS

SmartCompany is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while it is being reviewed, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.