The challenge faced by removalist company Kent will be familiar to many long established family businesses: how does a business founded in 1946 embrace necessary change without alienating employees and traditional markets and remaining true to the values which have sustained the business over such a long period?

The answer from chief executive Timothy Irwin: carefully, deliberately and, to paraphrase business oracles Roy & HG, always assume that too much internal communication is never enough.

Read more: How innovation revitalised a dairy company

Irwin is a 20-year veteran at Kent and it was in his previous position as national marketing manager that he spearheaded the company’s diversification into corporate relocation services 10 years ago. That division includes orientation and resettlement services for the families of relocated executives, visa and immigration services for international relocations, and a licensed real estate agency.

“It was quite a big change [for staff] to accept that diversification was in the company’s long-term interest. Engaging with staff, reinforcing the key messages about why we were doing this and ensuring that they were part of the journey was a critical part of the process,” he says.

“The key learning for me was that no matter how effectively you believe you are communicating with staff, you can always do more.”

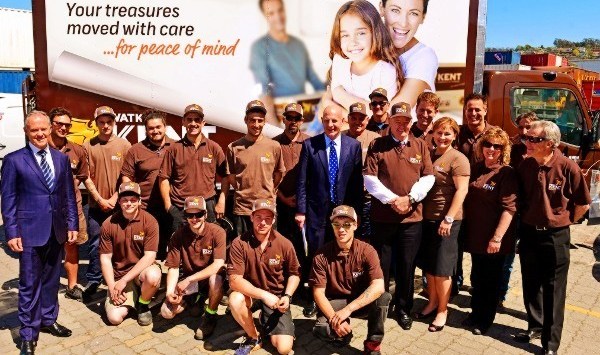

Kent has 500 employees nationally and has annual revenue of $100 million. Founded as a small furniture delivery business in the Melbourne suburb of Glen Iris by the late Keith Kent, father of current executive chairman Graham Kent, the company is into its third generation of family control: Graham’s son, former Macquarie banker Wayne Kent, is a non-executive director and Irwin married into the family.

The Kents knew that a family business’s transition from the second to the third generation can be problematic. Irwin was tasked with leading the change agenda, which he has been bedding down for the past five years as chief executive.

“In our industry sector, a lot of companies don’t make it to the second or third generation. If a company isn’t innovative, it will perish. Some really strong brands in our sector have fallen by the wayside because they didn’t innovate,” he says.

The diversification into corporate services – which accounts for about 10% of revenue – required the introduction of new skill sets and different disciplines into the organisation.

Irwin says integrating the new business into Kent’s operations was “definitely a challenge”, but having a core of long-serving employees provided Kent with valuable stability as the new division took shape.

Another important factor in the smooth integration was ensuring that Kent was still seen by staff as a single business, operating by the same set of vision and principles which had guided the company since its inception and which appear on the company’s website. The expanded business also meant new career opportunities for existing staff.

Know the limits of diversification

“Whilst I was bringing in new skill sets, it was also made clear to staff that there would be opportunities to extend their careers with the company; they might start with us in one part of the business but over time they could pursue a career path into another part of the organisation.”

The importance of communication and staff engagement in the change process was not the only lesson for Irwin. Knowing the limits of diversification has been another.

The addition of corporate services was successfully integrated into the business in part because they were a complementary extension of Kent’s core removalist and storage business. But when introducing complementary lines, where does one draw the line?

For Irwin, the answer turned out to be not as far out as the original expansion model projected.

When planning for the diversification into corporate services, Irwin looked to similar companies in the United States for guidance.

“As creative as we all are, the reality is that someone will have gone down that pathway previously. So my view was that we should learn from the market place what’s worked well and what hasn’t, and from a best practice point of view the decision was to look to the US,” Irwin explains.

“From a modelling point of view, there are a lot of learnings to be had from offshore, and it was valuable for me to look at the experience of companies in the US that I would consider to be my peers.”

When the business model for Kent’s corporate services division was drawn up, it included tax advisory and payroll management services for international relocations. Irwin hired three professional staff from Big 4 accounting firms and persevered with the business unit for 18 months before deciding this aspect of the diversification was “overreach”.

“There’s no question that the product [offering] was too complex. Technically, it was too great a diversification for us to integrate into the business,” he admits.

“When we looked at the US we perhaps didn’t take into account that their markets are so much bigger. It’s valuable to look overseas for growth and success stories, but it’s also important to adapt those learnings to the local market. It was a valuable lesson.”

‘Strategy-driven cultures work best’

Melbourne change management consultant Mark Schroffel says the most successful business transformations align a company’s culture with its strategic objectives.

“Strategy-driven cultures, with engaged and well led staff, work best,” he says.

“My advice to clients is to keep the objective front-and-centre and work through any fundamental changes in the business that are needed to support it – starting with strategy, culture and values, then align processes and systems. In the end, there should be a line-of-sight through all those elements.”

For South Australian jam, condiments and sauce maker Beerenberg, authenticity was the key to its culture and brand revamp.

Beerenberg is owned and operated by the Paech family. The business takes its name from Beerenberg Farm in Hahndorf in the Adelaide Hills which has been in the family since 1839, although the family has been manufacturing its products since 1971.

The business is run by the sixth generation of the Paech family to live on Beerenberg Farm, so it is not surprising that there had been some resistance to feedback over the years from retailers and distributors that people often mistook their products to be “European” because of the products’ labels. The farm’s name, the labels’ styling and the illustration of a German barn – a nod to the family’s, and the region’s, German heritage – overshadowed the products’ local provenance.

During a family strategy meeting in 2012, the issue of the labels came up again. This time, marketing manager Sally Paech recalls, it was decided to do something about it.

“The labels weren’t contemporary looking. We knew that ourselves, but it was our brand and we were proud of it, but we were getting that feedback from the retailers,” she says.

“Once we had decided that we were ready to make the change, the choice was whether to introduce change incrementally, or to take a brave and radical approach and change everything at once.”

The decision was to go all out – but not without consulting the experts. Beerenberg is an icon brand in South Australia, so Paech decided that the best way to capture the true essence of the business was to look interstate for a creative agency that would “see us through a new pair of eyes”.

She chose Sydney agency Tiny Hunter and the result was new labels for Beerenberg’s entire 65-strong product range. To underscore “the provenance of our farm”, each product is named after a family member or employee, each with a personal connection to the product. “There’s a real person behind every single product,” Paech says.

The rebrand took effect in mid-2013 and sales grew by 30% in the first 12 months. Importantly for Beerenberg, most of the growth was outside of its core South Australian market, in Victoria and NSW.

“We were attracting people that we didn’t attract before. We were getting emails from people saying ‘Now that we know you’re Australian we’ll buy your product’,” Paech recalls. “It just needed that fresh Australian brand.”

COMMENTS

SmartCompany is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while it is being reviewed, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.