Source: shutterstock.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an enormous impact on the global economy, with the total cost likely to exceed US$12.5 trillion ($18.15 trillion) according to International Monetary Fund estimates.

At the same time, the crisis has accelerated huge changes in the way we live and work, and the adoption and invention of new technologies.

Policymakers and leaders in science and industry are pinning their hopes on further innovation to drive economic recovery.

It is a good plan, but stimulating innovation is not easy. I have studied attempts to stimulate local innovation around the world over the past century, and found six broad approaches, each with strengths and weaknesses.

1. Place

This is the development of specialised high-tech clusters or hubs (think the next Silicon Valley). There is good evidence high-tech clusters are crucial for national competitiveness.

Industrial clusters (and cities more generally) are centres of innovation, productivity, skills development and new enterprise creation. Clusters aid both co-operation and competition between firms, build local supply chains, and can create regional brands such as watches from Geneva or suits from Savile Row.

Silicon Valley in California may be the world’s most successful high-tech cluster. Shutterstock

Many governments have tried to create these clusters from scratch with public research institutions, creating science and technology parks, or providing financial and other incentives. Only a few of these attempts have succeeded.

Attempts to accelerate existing or emerging industry clusters have been more successful. Building new industry clusters is also incredibly costly, and can take decades to pay dividends.

2. Culture

This approach seeks to build an innovative, entrepreneurial environment through enhancing lifestyle, culture, and public amenity. It seeks to create a “people climate” where residents can experiment, build, share knowledge and form creative partnerships. This should also attract and retain the young, creative, educated wealth-builders of the future.

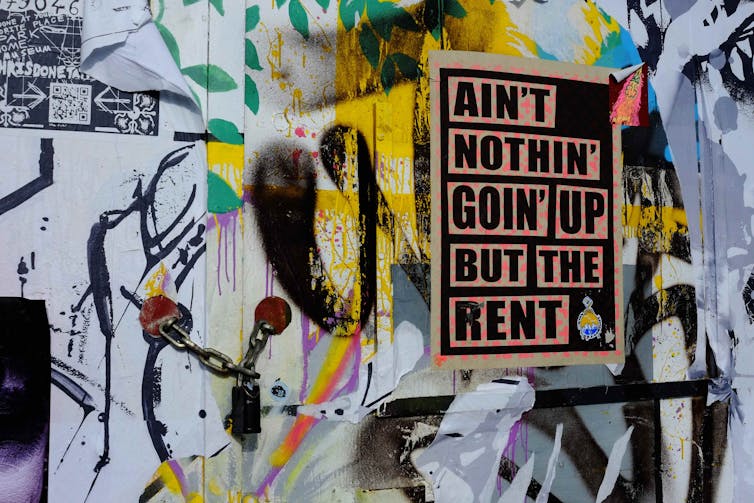

Attempts to revitalise inner-city areas can backfire, driving out the young and creative people they were meant to attract. Shutterstock

Urban revitalisation projects worldwide have followed this approach. These projects re-purpose downtown and inner-city areas into hip and trendy environments which encourage incidental interactions, casual conversations and group learning.

However, lifestyle enhancement doesn’t always lead to more innovation. It can lead to rapid gentrification, which displaces creative communities who can no longer afford the rising rents.

3. Skills

Another way to boost innovation is to increase the local level of valuable skills. This can be done by attracting skilled migrants or training up the local population.

The problem with focusing on skills alone is that people are mobile. Skilled people will leave if they’re not provided with ongoing opportunities, or if the financial, lifestyle or creative rewards are higher elsewhere.

Global competition for highly educated or skilled people with experience in creating successful ventures or products is becoming fierce.

However, skills-led approaches to innovation can be powerful as part of the “triple helix model” which integrates research, government, and industry. Critically, skills development needs to be matched with local opportunity.

4. Mission

US president John F Kennedy announced the US moonshot in 1961, but the mission was carried on by his successors. NASA

The mission-based approach pools private and public funding and skills to tackle a mid- to long-term challenge. The most famous example is the US moonshot: the 1961 mission to send a person to the Moon and back by 1970.

NASA had funding for the moonshot over three presidencies. The mission succeeded, and in the process it developed several new technologies and products.

Since that time, “mission statements” have become common in business and government. Governments and NGOs use missions and targets to inspire action on a range of challenges, from net-zero commitments and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals to developing vaccines for global pandemics in under 100 days.

However, missions can run into trouble through lack of ongoing funds, unclear goals, competing interests, and the generation of unintended consequences. Missions can also divert funding from curiosity-driven “blue sky” research, which has been responsible for some of the greatest scientific breakthroughs of all time.

5. Finance

One crucial element in boosting innovation is increased funding for research and development, universities and other research institutions, and commercialising new technologies. However, the relationship between increased funds and increased innovation is complicated.

As countries become more advanced, spending on innovation can become less efficient. Once early gains have been achieved from adopting existing technologies, further advances can only come from the more expensive and riskier processes of creating and commercialising new technology.

This pays off for countries with large markets and existing levels of high productivity, but is harder for other countries.

The venture capital that enables many emerging companies to expand rapidly is highly geographically concentrated. Venture capital also tends to focus on a few sectors, including the information technology and pharmaceutical industries.

6. Technology

This approach uses government spending to provide purpose and funding for new and emerging technologies such as drones, AI, blockchain, and robotics.

When governments engage with innovative local companies early, building their capabilities and co-developing technology applications, it can be good for government and industry. Government gets more modern services, while industry has a strong client.

This approach has built some of the largest and most successful innovation hotspots in the world, including Silicon Valley. The downsides of this approach are that it can gamble with funds allocated for other government purposes, embarrass governments when things go wrong, and relies on government being able to rigorously assess new technologies.

No magic bullet

Success in building vibrant, innovative areas at a local level is crucial for boosting and growing the national economy. None of these six approaches alone will be a “magic bullet” for innovation and economic recovery.

So what will work? Paying close attention to local contexts, and balancing all of these approaches: mixing and matching for local circumstances, while focusing on national productivity, technology development, and future markets.![]()

Alicia (Lucy) Cameron is a senior research consultant at Data61.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Handpicked for you

Is ESG really making a difference? Why everyone in your organisation needs to be on the same page

COMMENTS

SmartCompany is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while it is being reviewed, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.