Sam Webb and Caile Ditterich from BlockGrain. Source: Supplied.

It’s official: the more than 80% decline in cryptocurrency prices over the past eight months has officially trumped the dot-com bust of the early 2000s.

Back in the year 2000, the Nasdaq Composite Index’s plunge came in at 78% from peak to trough as share prices for tech companies collapsed. Cryptocurrency poster child Ethereum’s crash this year has well surpassed that, freefalling 87% from a high of $2,000 in January to $250 earlier this week.

Clearly, the dot-com crash wasn’t the end of the road for tech stocks, which bounced back with considerable aplomb and companies such as Apple, Amazon, and Netflix sit at some of their highest-ever valuations.

But even in at the turn of the millennium, technology was a mature market, whereas cryptocurrency is comparably still in its infancy, and concerns are rising over the longevity of cryptocurrency-related funding methods as they face constant scrutiny and overwhelmingly bearish sentiment.

Only in the past couple of years have initial coin offerings (ICOs) taken off, as cryptocurrency’s take on an initial public offering saw companies around the world raise millions in no time at all, in some cases providing companies with barely an idea and a website with instant millions in capital.

A number of Australian companies have benefited from the new funding methord, with projects such as Chronobank, Power Ledger, Havven, and CanYa riding the boom and raking in contributions from hopeful investors, with amounts raised stretching upwards of $40 million.

But with the markets on a significant downturn, local ICO activity has almost entirely stalled, as blockchain startups bide their time or even reconsider their options as new money becomes scarce.

Examples include local crypto credit card startup Moxy.One, which failed to raise the minimum needed for its coin offering earlier this year, while crypto-for-food startup Liven has significantly delayed its multimillion-dollar raise that was initially pinned to start in July.

The time is (not) now

Caile Ditterich is the founder of local agriculture-focused blockchain startup BlockGrain, which completed a $5 million ICO midway through this year from over 2,500 investors. BlockGrain’s ICO was one of the last to be completed in recent times, coming in at the tail end of the 2017-18 ICO boom.

Speaking to StartupSmart, Ditterich says his startup’s capital raise was “tremendous” and the company was very fortunate to get contributions from as many investors as it did. However, when asked if he’d attempt to do the same coin offering now, Ditterich was apprehensive.

“Right now, I think an ICO would be very hard,” he says.

“The market’s completely dropped, and the money previously in the industry is no longer there. A lot of people got burnt after buying six or seven months ago, so the fresh money that was flowing around is just not there.”

Ditterich also notes a number of crypto projects have been ousted as scams over the year, increasing the already high levels of distrust in the sector and making investors rethink participating in an ICO.

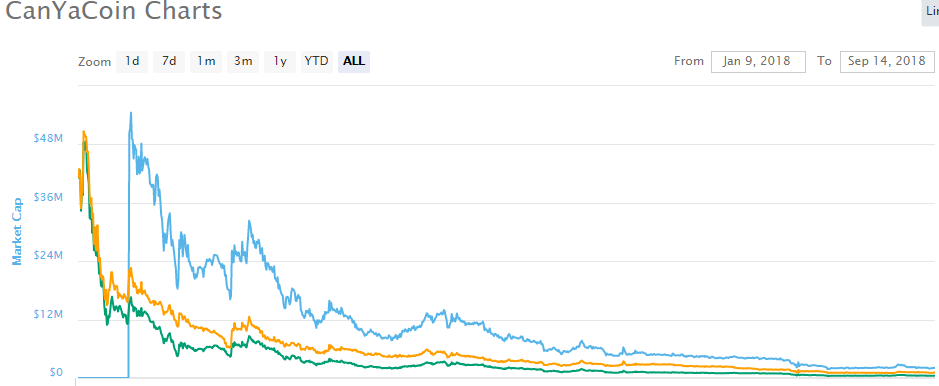

It’s not just Ditterich who’s seeing the blood in the waters, with CanYa co-founder JP Thorbjornsen agreeing it’s a “lot more challenging” to run a successful ICO now compared to late last year when CanYa ran its coin offering.

Thorbjornsen’s company was one of the earlier entrants into the Aussie ICO space, and managed to secure a very respectable $12 million raise for its crypto-focused online freelancing marketplace. The company has since been developing numerous additional expansions to the business.

The founder, who has gone on to be an adviser to a number of local projects, told StartUpSmart not only is there significant “noise” in the blockchain space, but base-level software such as Ethereum hasn’t been developing at the pace needed.

“There’s a lot more noise and scams in the scene at the moment, and there’s been a lot of disappointment in token sales. There’s also a realisation that the underlying, or first-layer, protocols being built aren’t mature enough, and the ecosystem is essentially delayed because we have to wait for that maturity,” he says.

The co-founder says launching a ‘second layer’ protocol — something like CanYa or Power Ledger — is something he wouldn’t currently be comfortable with, unless the development timeframe was stretched over a number of years.

The Canya Founders, JP Thorbjornsen, Kyle Hornberg, and Chris McLoughlin. Source: Supplied

Investors left “holding the bag”

However, it’s not just market actions and investor sentiment contributing to the recent downfall of ICOs. As valuations began to soar throughout the end of 2017, institutional investors and ‘big’ money were looking at the eye-watering gains, and deciding they wanted a piece of the pie.

But instead of investing on the ground floor via a typical ICO sale structure, the investors and firms with millions in their pockets went looking for a better price and began negotiating with companies over huge investments for huge discounts on their token sales.

This led to situations like the one surrounding Australia’s own Havven, where institutional investors and high-net-worth individuals dominated the majority of the company’s $40 million raise, leaving just $6 million in tokens available for the everyday investor.

Ditterich was not a fan of this prospect, choosing to eschew large-scale investors for the BlockGrain ICO and instead raising the company’s $5 million from only lower-level contributors.

He thinks the ICO market has become too “centralised” due to the prevalence of big-time investors and it’s another reason why crypto capital raising activity has died off.

“The idea behind a token sale is to give every person a chance to be involved, but what’s happening now is that companies are giving big investors huge discounts, who then leverage that once the tokens hit exchanges,” he says.

“The price then falls through the floor, and the people left holding the bag are the average investors.”

For Australian investors right now, their bags would likely be very full, and very heavy. Out of high-tier projects CanYa, Horizon State, Power Ledger, Havven and Loki, the only one still trading at a price higher than its initial exchange price is Power Ledger.

All the other projects have seen significant drops in value through public trading, with the most drastic being for Horizon State and CanYa, which have declined by 97% and 99% respectively from their highs earlier this year.

Source: coinmarketcap.com

CanYa’s Thorbjornsen isn’t fazed. He says the company “definitely” achieved its objective of building a strong community and advancing cryptocurrency adoption via its token sale.

“We have a highly engaged community who is excellent at giving feedback on our products and helping execute on our global go-to-market strategy,” he says.

“Another purpose was to raise funds via the ecosystem to develop our app for the global market. We’ve done that and we can continue to do that all thanks to the token sale.”

BlockGrain is yet to list its token on exchanges, with Ditterich saying the company is still assessing its options.

Are ICOs here to stay?

So while it’s pretty clear attempting an ICO right now would probably leave your business empty-handed and downtrodden, what does the long-term picture look like? Will ICOs continue to live on in the future, alongside loans and venture capital, as a convenient way of financing a business?

Both Ditterich and Thorbjornsen think they will; they’re confident the market will bounce as it has many times before, and money will come flooding back into the crypto and ICO space.

Michael Bacina is a partner at Australia’s premier blockchain legal firm Piper Alderman and has provided legal advice to all of Australia’s biggest ICOs. He agrees with the two founders but warns regulatory oversight is also more prevalent than ever, and is likely set to increase.

“Regulators in Australia and the US have gained a lot more knowledge in the past year and are starting to be more assertive in contacting projects and asking questions early, and in some cases shutting down offerings which are really offering financial products,” he says.

Bacina thinks we’re in the midst of a move away from “utility” or “currency” tokens and towards tokens that represent real securities and ownership in the business, rather than ones serving only to facilitate some part of the business’ product.

“I expect significant pivots towards tokens which represent a real ownership of an underlying asset or interest in a business, or what I call a ‘tokenised security’. Revenue sharing tokens, in particular, are something I’m really excited about as they can offer a transparent and highly automated, yet affordable, way to share risk in an enterprise in an entirely new way,” he says.

However, Bacina also notes with new equity crowdfunding laws just passed, startups might prefer to go down a safer route rather than wrangle with the uncertain world of crypto.

Looking forward, Ditterich isn’t concerned in the slightest and is getting down to business building out the BlockGrain platform.

“It’ll rebound. The tech is pretty proven and has a lot of potential,” he says,

“All the big players out there who’re saying, ‘don’t touch blockchain’? They’re already building their own blockchain systems.”

The author of this article was an investor in CanYa’s initial coin offering, and hold small stakes of multiple cryptocurrencies, much to his chagrin. He also briefly worked for Liven.

NOW READ: Ten Australian blockchain companies raising millions and disrupting industries

COMMENTS

SmartCompany is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while it is being reviewed, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The SmartCompany comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.